As AliceSoft’s Dohna Dohna ~ Let’s Do Bad Things Together finally releases on other storefronts, including JAST USA and MangaGamer, you may be considering trying the game for the first time.

Like most AliceSoft titles, it’s a tricky piece of media to recommend to those who aren’t already invested. Trying to explain Dohna Dohna in one sentence would give anyone who hears it the wrong impression. If someone suggested to you, “Check out this game about human trafficking,” you’d be forgiven if your first reaction was alarm. “A game where you do what!?” This is exactly the right question, and exactly the wrong one.

Yes, Dohna Dohna is a game about the illegal sex trade. It’s a story about people who made a horrible mistake, and a story about suffering, trauma, trust, power, and the cycle of violence. But even though it deals with intense subject matter, the writing has purpose, moral grounding, and a firm anti-exploitation message. Rather than a male power-fantasy promoting harm to women, it is a female-driven criticism of sexual violence, where it serves as political commentary. Leveraging its unique position as both adult-only material and an interactive role-playing game, Dohna Dohna delivers a surprisingly empathic portrait of abuse and exploitation, supported by careful writing and direction, that encourages us to ask ourselves “How could this happen?” and “Why is this wrong?”

Although scenes depicting sexual abuse are technically optional, they are home to most of Dohna Dohna‘s thematic content. The urge to avoid ‘bad’ content is understandable, since we often think of these types of games as having a ‘good’ ending and a ‘bad’ ending depending on which choices we make. But in this game’s case, to avoid the emotionally challenging parts is to not read it at all.

Dohna Dohna is a story about human trafficking, but it’s so much more than the sum of its parts. Why shouldn’t there be stories about that? This is why Dohna Dohna matters.

The episodic main story follows a group of young people who form something between a resistance fighter organization and a street gang in hopes of taking down the horrifically despotic government in Asougi City where they live. Kuma, a teenage member of one of three “Anti-Aso clans” called Nayuta, is the central protagonist.

Asougi perpetrates serious human rights violations against its citizens. Yet for certain reasons, the clans “snatch people off the streets by force and then hustle their bodies on those same streets to customers.” Within Nayuta, this is Kuma’s duty.

In addition, there are 13 short side stories, each focusing on a victim of this operation. They’re fully developed characters with arcs, hopes, dreams, and personhood. Although these “Unique Heroine” stories take place separately from the main story, they develop the central conflict between the clans and Asougi, from the perspective of innocent bystandersーaverage citizens.

During the main story, the other members of Nayuta endure their own abuse and are effected by what goes on. Often, their trauma directly calls into question the type of crime their clan is involved in through Kuma.

When dealing with severe subject matter, the thing that distinguishes the ethical from the objectionable is framing (rhetoric): how an issue is presented, and not just what the subject matter is. These issues are complex, especially because the protagonists are anti-heroes, and Kuma is responsible for traumatizing a massive number of women. The game respects readers’ intelligence by employing a clever solution.

Dohna Dohna is told only through dialogue, with no narration. This was a deliberate choice made to present events without judgment, so as never to condone something that shouldn’t be. Instead, readers are left to ponder characters’ words and motivations for themselves.

Dice Korogashi, in his ‘Alice’s Mansion’ (developer corner) statement, discussed how narration might have enforced a moral dichotomy where Kuma could have been glorified and his targets could have been labeled “wrongdoers.” A deliberate choice was made to avoid it. Director Ittenchiroku seemed to believe that the flow of the writing could have been disrupted by narration (such as if judgments were constantly passed).

ーDice Korogashi

The sole exception to this rule was during sexual scenes. Here, narration is morally sensitive, and harshly condemns acts of violence in both words and tone. Importantly, Scenes depicting sexual violence are predominantly, if not exclusively, written from the perspective of the victim, focusing primarily on the girl’s experiences. One of the most revealing scenes in the game is even written in first-person. This perspective choice turns the subject matter on its head.

Scene description contrasts abusers’ “bizarre, insane” selfish actions of domination, and degradation, and the victims’ experience of extreme trauma far at odds with the acts being done to them. It criticizes the destruction of the bridge of empathy leading to exploitation and violence.

Even though the Unique Heroines are dehumanized by other characters, their humanity is still respected by the text, which is an important distinction. They are portrayed sympathetically, and display positive qualities like honor, selflessness, bravery, and integrity.

When gameplay demands controlling the women Kuma traffics (or as he calls it, “hustles”), players are able to witness his mindset, how he has reduced women to data points, firsthand. Kuma manages the “talent” he keeps on a tablet in-universe, but players are given statistics and brief descriptions of each girl they possess as if they were noted by Kuma himself. Initially, it feels shocking to ‘accidentally’ get a girl pregnant and have to dispose of her, or for a girl to become “broken” mentally and not be able to perform anymore, but the longer the game goes on, players become as desensitized as he has.

In becoming so detached from their humanity, as well as his own, he ruins their lives without a second thought, much like the corrupt regime he opposes.

In the Unique Heroine events where the consequences of this operation are on full display, that comfortable apathy is shattered. The player’s attention is brought back so that those horrors are never forgotten.

Kuma convinces himself that he only targets Asougi’s alliesーpeople who further the regime’s goals and enable their oppression. But his illusory justification is immediately and repeatedly proven wrong; his evil actions mostly harm innocents who are equally oppressed and trying to survive just like him. Kuma is a villain driven by morally complex delusion and his insatiable hatred. He is wrong, and the text never shies away from this fact.

The very first Unique Heroine, Inui (encountered in Episode 2), is something of a ‘crash-course’ on Dohna Dohna‘s position on the issue. Because she sets the archetype for subsequent Unique Heroines to build upon, and effects how readers interpret and engage with future scenes of abuse, she is portrayed on no uncertain terms.

Inui is a student, the same age as everyone in Nayuta. She’s totally unaffiliated with Asougi and just trying to get by in the same society as they are. She places faith in her neighbors and believes in the inherent good nature of humans. She’s innocent, and this immediately reinforces that Kuma’s motivations have already spiraled out of control. When she is abducted, she is confused that something like this could really happen to her. Afraid, and in disbelief that anyone would do to her what Kuma says, she decides that she must be able to reason with anyone who comes for her, because people are good. But that is not what happens.

Unlike the aggressor, who speaks flippantly and is unmoved by her pleas, the writing empathizes with her terror and sense of being trapped in a place where no one would listen to her. The tone of these scenes is ‘suffocating’ and ‘tragic’ and in no way glorifies the abuse being done to her. In this way, it warns against the kind of cruelty depicted in this scene. Readers feel for the victim, in her shoes, rather than fulfill the fantasy role of a rapist.

In her next scene, which builds upon it, she is assaulted by someone from her neighborhood, who not only took advantage of her situation, but reveals to her that he had perverse thoughts about her that he kept hidden until he felt he could get away with it. Although this is something of a contrivance, it reflects a horrible reality that women face every day: the majority of perpetrators are someone known to the victim.

Inui has a firm belief in the implicit trust we place in others around us that keeps society running, which is especially true of a society like Japan, where high value is placed on social harmony and doing the right thing for the good of everyone. Her trust has been stripped away, not just in the individual people she knows and sees everyday, but the very foundation of the world she exists in.

Betrayal of trust is a very common recurring theme in nearly every Unique Heroine event, and for abuse in real life. An extremely common consequence for victims following trauma is the sense that the universe is no longer safe (or perhaps never was), and this theme is represented effectively by Inui’s story.

A range of emotional consequences of abuse inflicted on victims are portrayed, including their coping strategies and trauma responses, such as multiple instances of what can only be described as clinical dissociation. (This attention to detail alone was what first set Dohna Dohna apart to me as something truly special.) Rin is an excellent example. Her abuser is portrayed with a realistic motivation, and her scenes are artistic and tragic.

Other Unique Heroines elaborate on other issues related to sexual trauma.

These can concern abuse itself, for instance, the internalization of words abusers say to their victims, especially when the victim is forced to repeat them. The difference between willing and equal power balances and being forced into the sex industry (and the abuse of people in it), between something tolerable and something traumatizing. How self-effacement and people pleasing can make someone especially vulnerable to being taken advantage of. It goes on.

One of my favorites is a woman who was abused as a child, and, now going through a similar trauma to then, reflects on her experiences and achieves personal growth. She finds a reason to survive, not just for others, but for herself, despite her bleak and seemingly insurmountable circumstances.

One idealizes the Anti-Aso clans, only to come face-to-face with the truth that they aren’t heroes. Another serves as a parable for the commodification and objectification of women in the idol industry. A guard learns that she has been misled into being an agent of tyranny, and corrupt enforcement of the law has only created more evil in the city rather than protecting citizens from it.

This isn’t to say these scenes are totally without flaw or that there was no obligation to fulfill guest artists’ character specifications or eroticism, but there was a considerable, genuine effort to portray them delicately through a critical lens. At the root of it all are sincere intentions and a healthy view of this kind of abuse as nothing less than an atrocity. Even the things which might have been guest artists’ requests tend to turn into something symbolically meaningful (as in Fumi’s case).

The main characters exist at the boundary of adulthood but are very young, and that dynamic is an important part of the emotional realities Dohna Dohna deals with. They’re vulnerable to certain ‘more adult’ forces. The girls experience their own trauma and have to grapple with it. As a coming of age story, characters grow and evaluate their relationship with the good and “bad things” in the world. Their place in it. With different kinds of love, sexuality, and abuse. With crime and violence. With institutions, oppression, and the systems that govern the adult world.

In particular, they get into what they do for very human reasons that in real life may lead even well-intentioned people to be indoctrinated into horrible groups and descend into crime. Unmet needs, ostracization, vulnerability, pain… There is a progression for each of them.

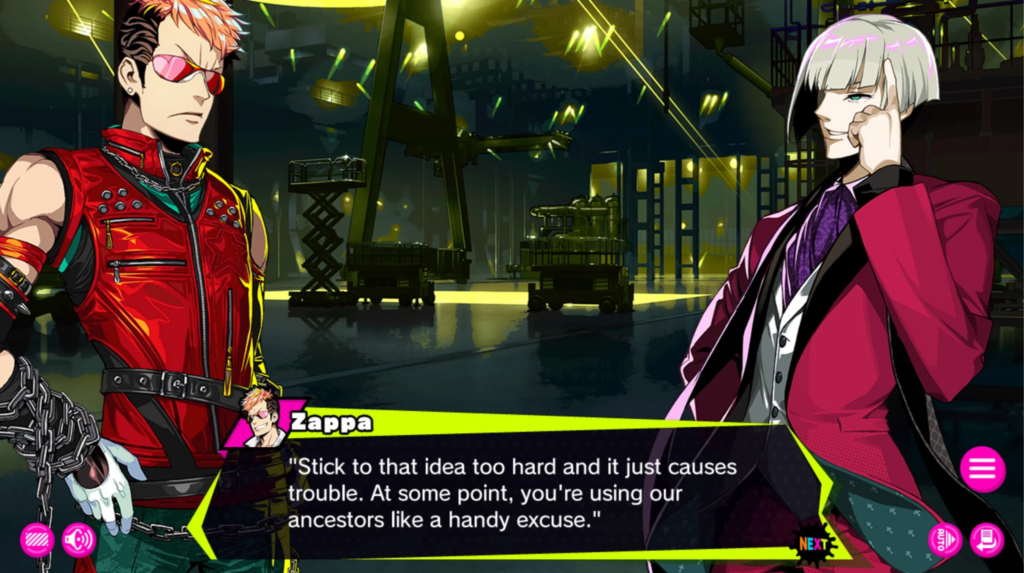

Their clan, Nayuta, was originally formed with an honorable mission by the characters Torataro and Zappa, and got into ‘ordinary’ mischief. Think vandalism, dining-and-dashing, crashing sporting events, and eating too much at a buffet to cut into Asougi’s profits. But due to certain influences, this doesn’t last long.

Later on, Kuma, the protagonist, joined. Kirakira, his childhood friend, knew him long before he ‘changed,’ and followed him, seeing the good in his heart. He saw joining an Anti-Aso clan as the best way to achieve his goal of bringing Asougi down. Of all the Nayuta members, he carried the strongest vengeance, and he set aside his morality in his pursuit of twisted justice at all costs, evocative of Captain Ahab and his white whale.

In short, Kuma was manipulated by someone who gained his trust into seeing human trafficking as the solution. Read on by clicking the spoiler box:

Kuma’s entire family was killed by Asougi in their human experimentation program, and they moved to target him next. He swore revenge, and became Anti-Aso in hopes of one day exacting it.

While blinded by hatred and traumatic grief, he met Mistress, an arms dealer for the clans, and she convinced him to get into the act of selling women. She preyed upon his emotions, and gave him manipulative justifications that he was in a place to be vulnerable to. Kuma is still young. It was most likely rationalized to him in the very same ways he repeats: as revenge, ‘damage to society,’ funding for his clan, and because he needed that, he believed it. It can be assumed that she similarly convinced the other clans by dangling their own needs in front of them, as well as calculated information leaks.

But Mistress also (falsely) promised Kuma his future safety, a trailer house for him and his friends while they’re on the run, if he does what she asks. Of course, she never delivers it to him, because she’s actually just stringing him along to her own ends.

She gives him assignments, and penalizes him financially for not fulfilling requests for “VIPs” (which, of course, compromises his future if he can’t afford that trailer house in time). Mistress got him into a deadlock. In reality, Mistress serves a high ranking Asougi official, and is responsible for a counterinsurgency operation which turns the clans into the public enemy to distract from Asougi’s own crimes and feeds the sexual appetites of the Asougi elite (those “VIP” clients).

Mistress is undeniably a groomer, both in convincing Kuma to do her bidding, and in the fact that she, as a much older woman, makes sexual advances on him, still a student. She pulled him away from his friends and coaxed him into the ‘hustling’ business to satisfy herself and her assignment.

In reality, it was ironic that he hoped taking Asougi down would ensure nothing like what happened to his family would happen to anyone else ever again. He rescues another main character from his own fate of human experimentation as a “body donor” out of sympathy. But, at the same time, he inflicts comparable heinous, life-ending suffering on countless women, feeding victims right back to Asougi. (When Kuma dismisses kidnapped women, he hands them off to mistress, who funnels them off to other Asougi divisions, where they often become body donors.) He becomes not unlike the villains he sought to destroy in the process.

In the end, he says his only reason was to get revenge for his sister, a motive that, while understandable, became just as selfish when it came at the cost of uncountable human lives.

Kuma brought ‘hustling’ back to Nayuta where it became ‘his’ designated role. He repeatedly tells everyone else not to get involved with this ‘business’ of his, because they could not fathom the severity of what he does. Initially, everyone is in denial but him (aside from one other).

The rest of Nayuta started with an idealized image of what rebelling against Asougi would be. As the story goes on, they have to contend with that it has become so much worse than they could have imagined. A promotional tagline for Dohna Dohna reads “What’s really the worst thing happening in this city?” What, indeed.

I would compare the role of the main heroines to that of Jesse Pinkman from the television series Breaking Bad, who remains sympathetic despite Walter White’s increasingly heinous actions, and bears a different sense of culpability.

There is a sense that something has ‘changed’ about Kuma among his friends by the time the story starts. He becomes obsessed with his so-called work, and, suppressing both grief and his horror at his own actions, he fails to express emotions or even relate to his friends anymore.

Kuma’s conduct has devolved into sociopathy. When addressing the girls under his control, he speaks in the most inhumanly cruel way he can come up with, far out of character for anyone his age, that would terrify his friends if they knew. It’s an act, but he’s in danger of becoming it.

As Kuma operates this ‘business’ and players move through the game, his cognitive dissonance is experienced firsthand by the player. A reader can follow his sense of guilt, question how he made these mistakes, and learn from them.

Across the Unique Heroine stories, Kuma reaches a moral nadir, but gradually regains (some of) his mercy as his friends endure their own pain.

His perspective changes as he tries to help his friends heal while at the same time traumatizing others, creating a compelling point of conflict.

The final Unique Heroine story ties all of this together. Read on by clicking the spoiler box:

Eventually, Kuma puts the final Unique Heroine through the ultimate atrocity, and afterward, learns about her previous trafficker. Seeing his own actions from the outside, and forced to face the monster he’s become, he finally realizes the true depravity of his mistake. He goes to free her, but she has already escaped; the narrative deprives him of any redemption. It’s too late.

Even wordlessly, without narration, the implications of this moment, as the conclusion to the final Unique Heroine story and this entire side to Kuma’s character arc, are powerful.

After this, Kuma repents the only way he still can: by showing compassion to his deeply wounded friends. Going by unlock order, the following scene could be interpreted to take place after that event in a timeline, and after Antenna experiences something awful that Kuma witnesses the video evidence of:

Only one other member in Nayuta is as acutely aware as Kuma is about the egregiousness of the acts he’s committing. Read on by clicking the spoiler box:

Shortly after Nayuta’s formation, they raided another organization trafficking women called “Reach.” There, he rescued a girl and took her in. She took the name Porno.

Porno’s trauma is quite recent by the time the game begins and she is dealing with it in an unhealthy way. She struggles with hypersexuality, and while Kuma is her attachment figure because he saved her, she tries to seek attachment under the pretense of sex, because it’s the only way she knows how. Across all her Feeling scenes, she tries to take different roles, re-enact what she learned from her exploitation, and change who she is, all to find what would make Kuma love her. It may sound corny, but this resolves when she stops objectifying herself and connects with him honestly.

Her idea of what sex should be like is distorted as a result of her abuse. Porno could be described as enacting her trauma on others to reverse the dynamic and reclaim a sense of ‘control’ over it, over the feeling of powerlessness it caused her, and because she was made to do it for so long that she thinks it’s the only way to survive. Seeing it as her only skill, she “helps” Kuma with his ‘hustling’ operation (as an advisor, in ways other than getting directly involved with the girls Kuma holds captive.)

Over the course of the story, she confronts her own PTSD and the detrimental attitudes that led her to act out, and she grows and becomes more healthy. Eventually, Porno emerges as one of the most empathetic figures of the main cast.

In her ‘Feeling event’ side story, Kuma confronts the man responsible for her trauma. This is the first in a series of incidents that cause Kuma to reflect on what he has done and who he is becoming. The other most significant event is the assault of his childhood friend, Kirakira.

Other main characters have their own reasons for taking part in Nayuta’s operations. Medico’s belief in the inherent trustworthiness of both institutions and other people made her easily swayed by Nayuta’s apparently kind behavior amongst themselves. Meanwhile, she is so horrified by the reality of Kuma’s business that she becomes physically sick.

When Nayuta reached an electronic roadblock they were unable to deal with, they decided to ask Antenna to join for her technical skills. Kirakira used her position as Antenna’s best (and only) friend to convince her help them, and she accepted immediately, without fully understanding what she would be a part of. As an autistic girl forced out of school by bullying (and stalking/sexual harassment from a much older adult), she’d been so alienated all her life that she only wanted friends to value her as an equal, even if it was ultimately for help with something evil.

“….It kinda makes me feel like I’m okay.”

Kikuchiyo has a pre-existing commitment to her family to liberate the city at all costs. ALyCE and her sister YAMMy, who were previously trafficked for combat as mercenaries and forced to kill, needed a safe, loving family in any form. Joker no longer had a family and was being exploited by Asougi until Kuma rescued him, which led to him idealizing Kuma despite his horrible actions.

There isn’t a simple reason for their choices. It’s a complex array of factors, character flaws, influences, unmet needs, and grave (and human) mistakes, rather than the shallow, game-y justification that “they need money, Asougi is bad, and so-on,” that it may appear.

One critically important aspect of Dohna Dohna that some may unfortunately not aware of are the Variant B “Feeling events”.

As you progress, you raise a characters “Feel points” by battling with them or giving them items, and every 1000 points, you unlock a Feeling event for that character. For the girls, a lot of these are H-scenes, but there are also talk scenes too. These develop their own personal character arcs and relationship with Kuma.

However, at certain points in the story (see the CG Guide on the AliceSoft Wiki), the heroines might be assaulted in a “Bad End” event. These scenes are important on their own, but if they are triggered before ever viewing a single Feeling event, the text of one or more of their Feeling events is altered, sometimes radically, to account for that incident being canon. Their ordeals are talked about and the characters are deeply affected by them. Not only that, but the other Feeling scenes are already written in such a way that even the ones not literally changed take on new meaning.

(Here is a guide with more information on how I recommend approaching the game!)

Surprisingly, characters are sensitively portrayed as having post-traumatic stress disorder. They respond to specific triggers from past events and the text shows this by calling back to lines or ideas from previous scenes (even subtly referencing quotations at times.)

They fixate on certain aspects of what happened to them, or struggle with self blame. Porno has nightmares. But it goes beyond that: for example, as Porno discovers that sex can be a healthy expression of intimate love rather than means to an end or a recreation of abuse, she experiences new sensations she mistakes for a panic attack and has to somatically expose herself to them. She also realizes that she doesn’t have an overpowering need to be in control to cope anymore.

Porno is also implied to have an eating disorder, which is undoubtedly related to a specific part of her trauma she describes. Even a minute detail, like Porno being mentioned to pull frequent all-nighters, relates to how during her trauma, she wasn’t allowed to sleep, and was woken up violently, which would have left her afraid to go to bed.

Kirakira is one of my favorite characters (ever). From the beginning of the story, she tries to view herself as a mature adult, with a sense of newfound liberation that many her age have, and overestimates her capability to make decisions she can manage, and look after herself.

In reality, she is one of the most naive members of Nayuta, and truthfully afraid of taking anything too seriously. Not only would it cause her anxiety and pain, which she believes she’s not able to cope with, but she feels she has to hide what she’s going through so that her friends don’t worry for her–and she can convince herself she is the figure of maturity she aspires to be.

But, when she is assaulted, she has to contend with the fact that she wasn’t as self-assured as she believed, and admit to herself that she was afraid.

Medico starts out using sex to self-harm, going so far as to try to re-enact her trauma, but eventually overcomes her fear of sex and men, and experiences sexuality as something pleasurable, or even empowering.

Kikuchiyo deeply internalizes what her perpetrators said to her during the assault. She believes that Kuma would be disgusted with her and wouldn’t want to be with her now that she’s been “violated”, because these words were part of her trauma. She was told that she would reek of another man, and so she showers excessively before her first encounter with Kuma. In a heartwarming subversion, at the end of her and Kuma’s scene, she reflects on Kuma’s smell as something she’s okay with, and Kuma remarks that he can still smell her pleasant aroma on the sheets when she leaves.

With each heroine he comforts, Kuma regains his empathy more and more. When the Unique Heroine’s side of the story and the variant B ‘route’ of the main heroine’s side of the story are taken together chronologically, Kuma’s character development and the message of the work become strikingly clear.

A game bent purely on fetishizing abuse would never have gone so far as to include such dialogue.

But why depict this type of abuse at all? Well…

In the story, Asougi is an authoritarian regime, propped up by its own propaganda and suppression of dissent. The severe human rights abuses they conduct against their citizens include arbitrary arrests and enforced disappearances…

… as well as labor camps, medical experimentation à la MK Ultra, development of bio-weapons, etc.

Everything is for the state. The people live in fear and are effectively held hostage by their own government.

As an antagonist, Asougi represents the interests of fascist governments at the expense of the governed, the abuse of authority by law enforcement (especially as it serves state goals), false flag operations, planting of bad actors among protesters, censorship in schools, international manipulation with financial dependence and weapons of mass destruction, and other issues that appear within the narrative.

But above all, Dohna Dohna’s most important points concern the human cost of the global economy and the victimization of innocents in power struggles.

For example, some of the people Asougi traffics are exploited not just for sex, but for industrial labor and the production of cheap goods.

The juxtaposition of economic fascism and sexual violence (especially human trafficking) is precisely how Dohna Dohna makes its point about both: the root is power imbalances, lack of empathy, and selfish exploitation. Parallels between viciously authoritarian regimes and ‘ordinary’ abusers are drawn at every turn. The same people responsible for oppression of their citizens are also individual abusers and rapists, for the same reasons.

The story is a two-directional metaphor linking those issues, but also an acknowledgement of the very real fact that sexual violence is a facet and consequence of sociopolitical turmoil. It has relevance both to the global rise of authoritarianism and the human rights abuses occurring in the PRC in particular.

It’s an exploration of parts of fascist playbooks if fascism spread to democratic societies, in this case, Japan is the example. Asougi City was once a sovereign city Asougi forcefully subsumed… sound familiar?

This could be extended to corporate interference with political institutions, and the trend toward centralization (even in information technology, which happens to be referenced explicitly in the lyrics to the opening theme).

“Dive onto the train, now I’m drowning in ads”

飛び乗る電車の中 流れる電子広告

“I wish all this data would just disappear”

消えちゃえ モニター越しの情報

“Why doesn’t everyone think this is weird?“

違和感って思わない 周りはどうして

(Dohna Dohna no Uta)

Nayuta themselves serve as a symbol for individualism and self-determination.

It might be argued that this goes even further (notice a prominent American flag in Nayuta’s base) to say that in such a complicated world, there are no true heroes and even forces for ‘good’ can be guilty of evil in their methods and aims. (Also, America is called out by name, twice, on issues of gun control in comparison to Japan.)

In general, Dohna Dohna argues a lot of its points in a “how would you feel about this issue if it happened to you” type-of-way, calling out the gap between victims, perpetrators, and apathetic or ignorant bystanders. Certainly, that can extend to problems on the global stage as well.

One of its core themes concerns the bystander effect, “a social psychological theory that states that individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when there are other people present” (Wikipedia) and its role in facilitating things like… human trafficking.

Another is scapegoating as it happens under oppressive systems; those suffering are prone to direct their suffering on each other as they are powerless against the real cause of their pain. They might do anything to retain a sense power or control, even prey upon the weak.

These issues are particularly relevant to the most victimized group of characters in the game: Unique Heroinesー”hustling” victims. Their perspective on the conflict is that of innocents unjustly caught in the crossfire.

It is a cautionary tale warning us not to let propaganda lead us to misplace blame. Not to let division and infighting fester, when the ruling class and lobbying groups (chiefly corporations) are responsible for pitting civilians against each other so they don’t know who the real enemy is. That those in charge do this only for their own selfish gain in ways that, as ordinary citizens, we may never be fully aware of. It stresses the importance of solidarity among oppressed groups.

As a game evidently targeted to today’s young adults, which notably began development in 2016 and released in November 2020, it reflects existential anxiety about the effect global democratic backsliding has on future generations as we have grown up in a society that has never been safe for us, unraveling at the seams. It is a reminder never to forget the true cost of that inflicted on youth, but it also honors their resilience through a bit of escapism.

Dohna Dohna, is a game made in the spirit of protest, whether against the Chinese Communist Party, or anywhere in the world we are fighting autocracy and fascism in this dark era of human history.

“The minority’s on its way up”

マイノリティーって途上

“We’ve got so much room for it”

伸びしろしかないんじゃないかな

(Dohna Dohna no Uta)

Toxic masculinity, misogyny, malignant parenting, and even pornography addiction are called out as specific problems that contribute to sexual violence, portrayed through multiple characters.

The man who assaults Kirakira, Moriyama, is motivated by a sense of male entitlement to womens affections. He procures a firearm to intimidate her and feel power, and his two friends see him as that masculine ideal of “power” and aid and abet him.

The personality of Moriyama’s father, an arms importer for Asougi who gave him that gun, is explored in a succeeding scene. Based on his behavior, Moriyama’s upbringing is implied to have fostered his narcissistic complex and empowered him to assault Kirakira.

It is revealed that his father has a porn addiction which led him to urges to subjugate women. As pornography distorts his views on womens’ humanness, he needs more and more extreme brutality to get off. His addiction directly contributed to his willingness to inflict abuse (and seek out commercial sex acts). Although something despicable is being depicted here, its critical handling actually reflects feminist positions on issues of misogyny and gender violence.

In the Unique Heroine Tamaki’s story, her friend Shouta takes advantage of her plight because he is encouraged by his friends and his father to “be a man and make a woman his.” Relieved that she’s been paired with her friend and not a violent stranger, she believes that she can at least have consensual sex, but Shouta still disregards her wishes and hurts her anyway because he feels he has the right to. These characters are all reprehensible and portrayed in decidedly negative lights for their choices.

A main character, Torataro, also had a bad upbringing from which he learned toxic beliefs. But, when he says something wrong or harmful, he is admonished and corrected by his friends, and he has to take responsibility for his behavior. He becomes more caring and dependable.

In the spirit of protest, I’d like to leave you with two statistics about prostitution in general, at least as it manifests in the United States.

- In an ABC news poll, at least 15% of American men have admitted to paying for sex at least once, (Source 2) but research suggests this is a serious underestimate.

- Studies have found that 68% of prostitutes have been raped since entering prostitution, and 83% were victims of physical violence.

Taken together, I ask you: how pervasive is the problem in our society? What sways people to see human beings as consumable objects worth only the money they paid for them? How many harbor the opportunistic potential for this type of violence, even those you wouldn’t expect? I can tell you: too many.

Consider this: how is real life pornography produced? How much of that pornography is produced through human trafficking? Could you even know by watching it? Is it morally acceptable to consume it? What are the people in that video really going through, and can they ever forget it as you do when you turn it off?

If you would like to read it, I discuss these points and others in this piece.

Dohna Dohna‘s seriousness doesn’t preclude it from also being enjoyable. A game can be fun and serious at the same time, or erotic and critical at the same time. These things can coexist, as the entire work is built on the coexistence of good things and bad things. Sex and trauma, kindness and evil, cleanness and dirtiness, right and wrong.

Aside from the horrible trauma and abuse in the story, there are also themes of trust, friendship, and acceptance. Nayuta’s members find somewhere to belong when no one, and nowhere, else in the world was safe for them. Desperation and pain lead them down a dark path, but their feelings are human and relatable. There are plenty of scenes where things are calm. They get along in ways that seem to possibly draw upon the authors’ own interactions with friends growing up. Beneath their flashy designs, characters in Dohna Dohna have a striking authenticity.

It’s these light moments of humanity that make the suffering mean something. This is a common philosophy not only of all writing, but for eroge in particular, traceable to Key’s seminal formula of beginning in normal life and introducing conflict for emotional impact.

In many ways, Dohna Dohna corrupts traditional moege tropes, using familiar ‘language’ to tell a different, more grim type of story. Here, takes on common moege character archetypes are thrust into horrible situations they don’t belong in. It gives the game a charming ‘familiarity’ while characters’, and readers’, comfort zones are pushed to the limit. We expect it to be played safe, only to find that there’s so much worse in the world; what we know is wrong. The use of these tropes serve the theme, while paying homage to the medium it exists in and placing itself firmly among those works.

It’s a ‘romance’ game not for the well-adjusted students who found love under the cherry blossoms, but for the kids who grew up broken, got into dangerous situations, and didn’t fit into the life expected of them. Even for girls like myself whose first sexual experiences were not what they should have been. (Dohna Dohna has a sizeable female following, and I doubt its for no reason.) It’s still an escapist, troublemaker friend-group fantasy, sure. But it’s one that acknowledges, and somehow finds a way to appreciate, even the ugliest parts of growing up as a maladjusted teenager.

It’s personal, but I had never felt so heard by a work of fiction before Dohna Dohna. It helped me accept myself and heal from the things that I’ve lived through and seen. Nothing had ever told me “I’m sorry” for what happened to me quite how this eroge had. That it mattered. That I could honor that I was just a kid.

The way some scenes in this game were written made me feel like I was truly understood for the first time by an author, in a sea of media that stereotypes certain problems. Characters here remain humans first, and victims second. They are clearly not defined by the ways they are degraded. Raw details are ignored a lot of the time in other stories, but Dohna Dohna put to art experiences I’ve tried and failed to express on my own.

It’s okay if something bad happened to you. “You’re still the same person you were before.” If you feel like you don’t even know who you were before, like Porno, you’re still a whole person, there is so much more to you than that, and you matter. It’s okay if you messed up and got traumatized. It’s okay if you couldn’t finish school, or society doesn’t accept you, or the world never felt safe.

What I took away from Dohna Dohna was that it was okay to be me.

Maybe my appreciation for it speaks to how few other things like it I’ve really consumed, but to me, this game was everything. The stupid, silly, junk-food, fun eroge aspects of it made it tolerable and not just triggering. It’s far from perfect, but when I saw certain lines in my native language for the first time, for a moment I couldn’t believe what I had just read. I’ve accepted the few lines I do find weird or offensive as sacrifices for all it does so right as a whole. And for what it represents.

This game isn’t just edgy jerk-off material. Beneath its exterior, Dice Korogashi crafted something truly special. The script is so meticulous that, even after twenty-odd playthroughs, a new detail surprises me each time I read it. I know I’m not crazy, because he included this line at the end of his “Alice’s Mansion” developer corner.

Thank you very much for writing it.

I encourage more people to give Dohna Dohna an honest chance, even if they wouldn’t normally play something like this, in case they find something meaningful to them within it. I certainly didn’t expect an eroge to go to these lengths, but I’m so grateful it did. It changed the trajectory of my life, and it’s my favorite piece of media in the whole world.

Dohna Dohna is a lot more nuanced than it may appear on the surface. A first impression of what the game is ‘about’ doesn’t convey what the experience of reading the game is like. In reality, its a deconstruction of forms of abuse and the things that perpetuate it, as well as a political allegory, dressed up as a shiny eroge. It deserves to be approached with an open mind. Dohna Dohna is an exceptionally brave work of art with something to say and a reason for saying it. My hope that more people will be able to hear it now that it’s available to a wider audience.

If you’ve decided to give it a try, you can now buy Dohna Dohna on these storefronts by clicking the links below, DRM-free, at a newly reduced price of 34.95 USD! (18+ Only)

MangaGamer ・ JAST USA ・ Kagura Games

Dohna Dohna and its content as it appears in this article is the intellectual property of AliceSoft (Champion Soft), Shiravune, and any other rights holders. CG © ALICESOFT

This article was not written in association with any provided review code or promotion. The author is not affiliated with AliceSoft or Shiravune. Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily represent those of AliceSoft, Shiravune, or their staff.

The characters in Dohna Dohna engaged in sexually explicit activity are 18 years old or older, and this is clearly indicated on every store page where the game is sold, as well as provided for by the Ethics Organization of Computer Software rating the game received in Japanese and English. (More information)

It is the author’s opinion that this article is not itself sexually explicit.

I loved this essay so much! I really vibed with the themes going on in Dohna Dohna from the start and you expressed a lot of those ideas very eloquently here. I was also really surprised by the amount of sympathy and emotion tied around the various scenes of assault within the game. As a CG collector, viewing those bad endings was legitimately gut-wrenching due to the emphasis on the victim’s POV. Thank you for taking the time to present to the public what makes Dohna Dohna such a fascinating eroge.

Loved this think piece from farside. I think even without having played the game (yet) myself, the way the ideas are presented here and are given substance through examples of in-game dialogue are both empathic and greatly validating to people who might just resonate with themes discussed in the essay. It’s an incredible feat as a writer to be able to share your experiences and move people who might stumble upon this amazing read.

Thank you for showing us the beauty you’ve found in the game. I hope that more people become interested in trying out Dohna Dohna.

I see your attempt to ruin Dohna Dohna, but nuh. The game is still very fun. Almost as fun as your article. It’s just wonderful.

I understand taht you’re girl, so it’s not really game for you, but still)

“Rather than a male power-fantasy promoting harm to women” – yeah yeah, video games cause violence, school shootings happen because of GTA, bla bla, we’ve heard that.

“How much of that pornography is produced through human trafficking?” – ehh, barely any.

“Studies have found that 68% of prostitutes have been raped since entering prostitution, and 83% were victims of physical violence.” – yep, thanks to people like YOU. You are the reason prostitutes get raped. Because they can’t work legally, they can’t go to police, because prudes want them to be illegal.

“In an ABC news poll, at least 15% of American men have admitted to paying for sex at least once. What sways people to see human beings as consumable objects worth only the money they paid for them?” – oh no. I should probably also stop paying humans to get haircut or uber delivery or pay for any service to anyone ever.

“What are the people in that (porn) video really going through, and can they ever forget it as you do when you turn it off”. XD I’m crying here. Oh, my sweet summer child. No one forces those ladies to star in porn. If for some reason they didn’t like it – well, next time they should think before agreeing to a job. It’s called “being an adult”.

Also, most of porn today is home-made. If some lady loves to be a submissive girl engaging in a degrading male-dom sex and she wants to record it for pornhub (real life example) – is that also a problem for weirdos like you?

Really, the feminists’ ability to turn anything sexual into deadly sin is fascinating. I saw one article saying that blowjob is sexist and women should refuse doing it.

You all should find a real hobby, instead of trying to spoil other people’s fun, just because you’re miserable.

dude she literally says the game is fun in the article

do you think kuma forcing girls into prostitution is a good thing??

in any case i’d love to attempt to respond to some of the things you’ve said:

> “Rather than a male power-fantasy promoting harm to women” – yeah yeah, video games cause violence, school shootings happen because of GTA, bla bla, we’ve heard that.

my guy she is saying the game isn’t that, come on

> “How much of that pornography is produced through human trafficking?” – ehh, barely any.

> No one forces those ladies to star in porn.

her point is literally explained in the next sentence: “Could you even know by watching it?” so many pornstars come out of the industry with regrets, a loss of sense of self, etc etc. this isn’t trafficking per se but so many are put under contracts that they can’t do much about and come out of wishing they had never done so (not saying this is true for all, just that it does happen). there was a big situation on pornhub a few years ago proving that a significant proportion of the porn on there did involve non-consenting participants – again, perhaps this isn’t exactly trafficking, but it should be concerning nonetheless, no?

> Also, most of porn today is home-made. If some lady loves to be a submissive girl engaging in a degrading male-dom sex and she wants to record it for pornhub (real life example) – is that also a problem for weirdos like you?

it did not appear to me that the author wanted to limit people’s personal agency – if someone wanted to participate in the example you provide, that is their own decision, and they should be allowed to make their own decision. they should not be forced into the situation.

> “Studies have found that 68% of prostitutes have been raped since entering prostitution, and 83% were victims of physical violence.” – yep, thanks to people like YOU. You are the reason prostitutes get raped. Because they can’t work legally, they can’t go to police, because prudes want them to be illegal.

> “What sways people to see human beings as consumable objects worth only the money they paid for them?” – oh no. I should probably also stop paying humans to get haircut or uber delivery or pay for any service to anyone ever.

i can’t speak for the author’s beliefs on whether prostitution *should* be legal because she (as far as i saw) did not address it in this article. what she did say is that those in the industry *do* get raped and *do* face physical violence, and i’m so glad we agree that this is a bad thing

her second point here is true of hairdressers and uber drivers and others – you wouldn’t abuse them or do things outside of what is “expected”/”allowed for” right? she’s not saying prostitution shouldn’t be a service that one can pay for, just that you should respect personal boundaries

> Really, the feminists’ ability to turn anything sexual into deadly sin is fascinating.

when did this author’s article do this? i might have missed it 😅

sorry for the wall of text, i don’t know if you’ll even ever see this, but i hope this helps?